The origins of lost-wax casting (“cera persa”) date back to ancient times. Great civilizations such as Egypt, China, the Ancient Near East and Pre-Colombian America made use of it either by inheriting the technique from earlier cultures or rediscovering it on their own.

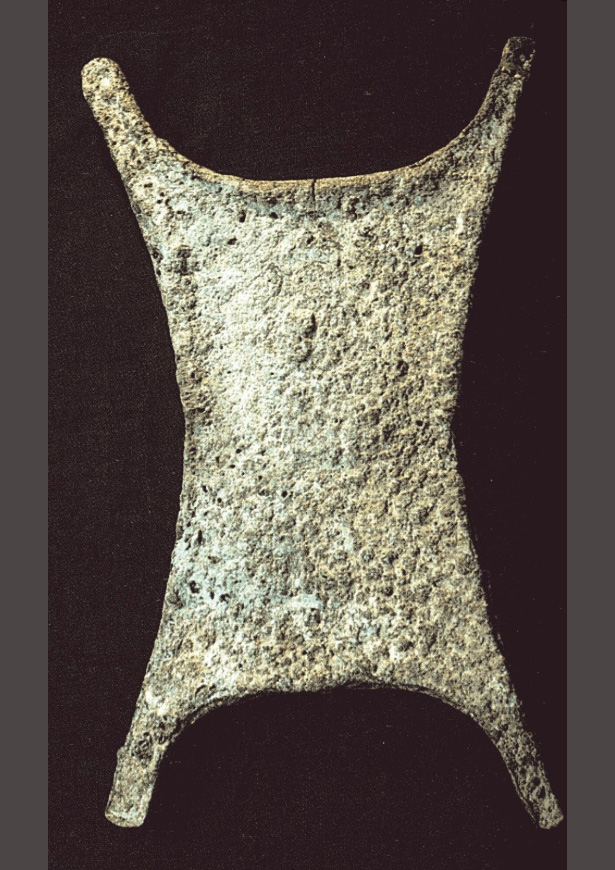

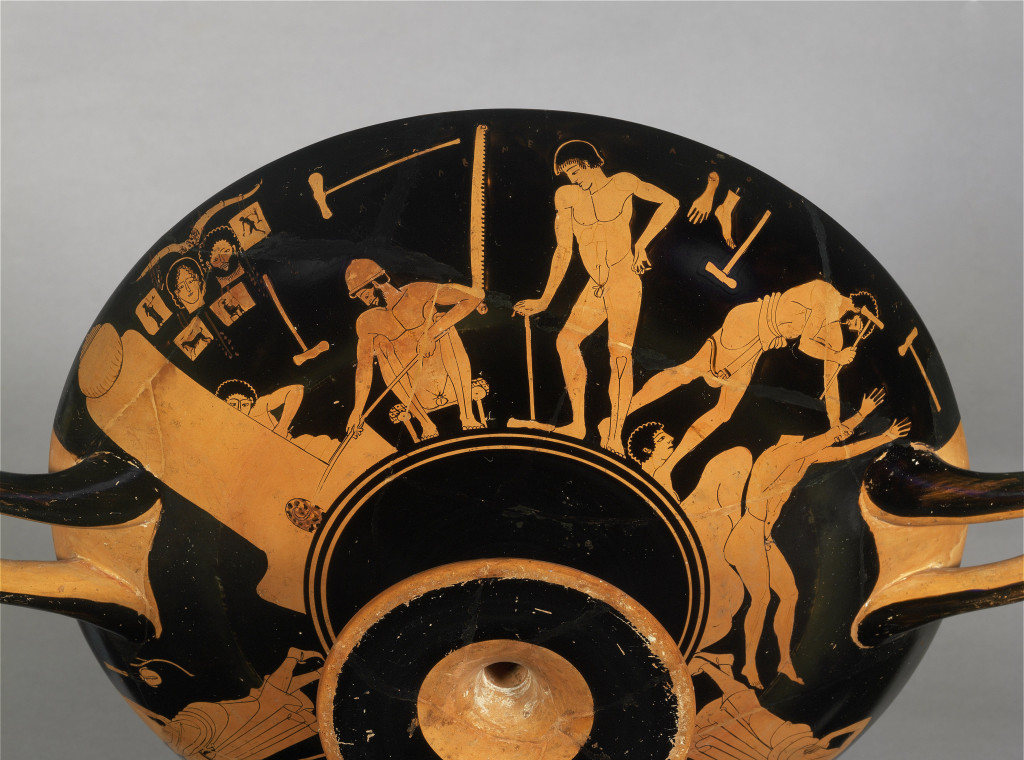

In Eastern Europe there were copper mines and foundries (copper is the primary component of bronze) as early as the 4th millennium. In Archaic Greece, even more in the Classical period, an extensive network of foundries existed as is testified by remains found near the Temple of Apollo in Athens where monumental statues were fused by lost-wax casting.

Greece bequeathed the technique to Rome where bronze working was already practiced by Etruscan sculptors, authors of such masterpieces as the Chimera d’Arezzo, the Minerva and the Aulus Metellus, known also as ‘The Orator’.

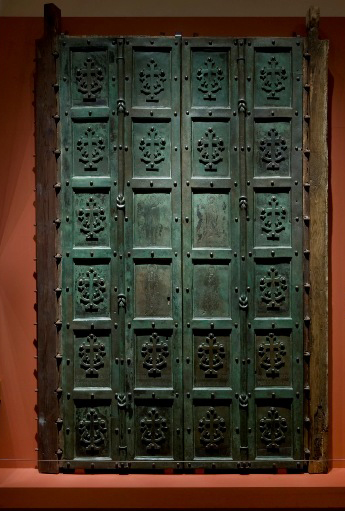

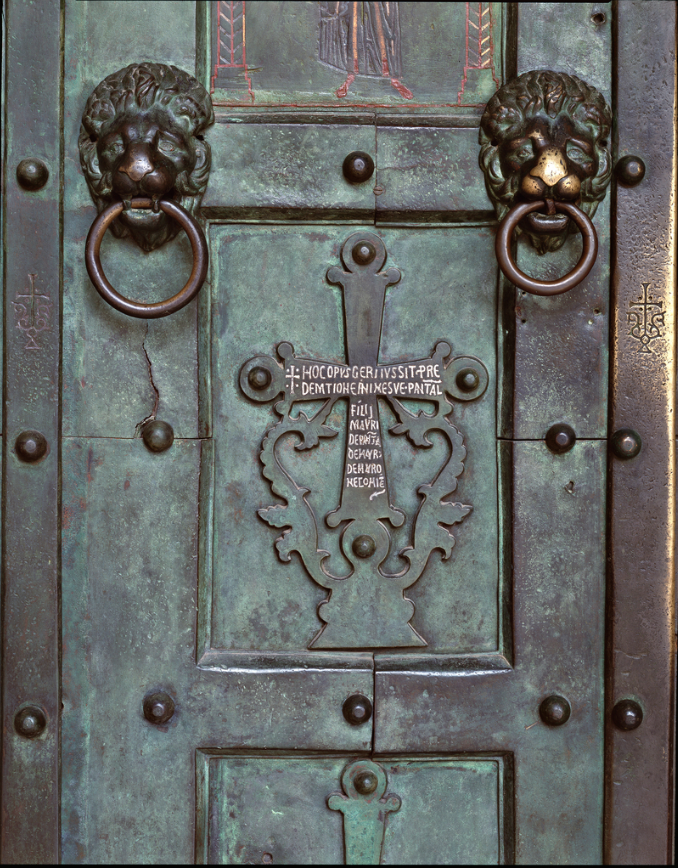

Roman castings were very popular throughout the empire however only those which represented Constantine, the signatory of the edict which permitted freedom of worship, were recast by the early Christians.